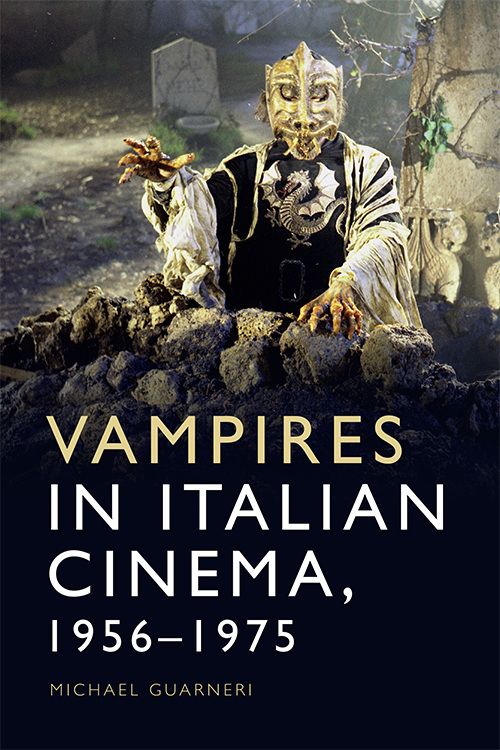

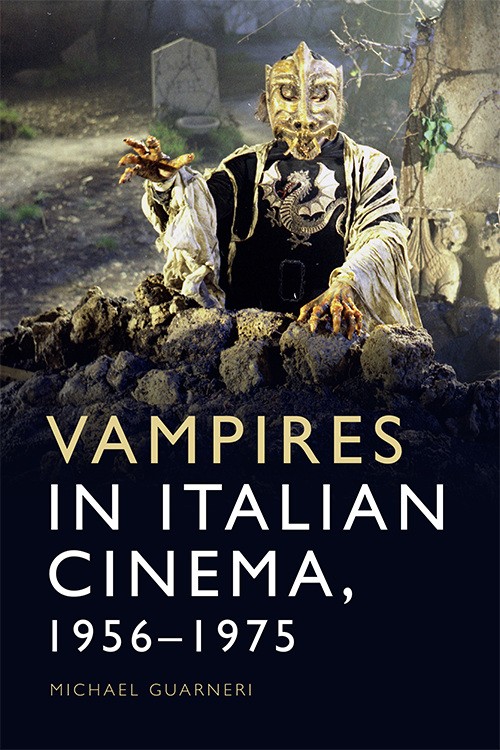

This is the English translation of an interview with director Mario Bava conducted by Luigi Cozzi. Luigi Cozzi’s questions are omitted in the original text, so Mario Bava seems to speak freely, stream-of-consciousness-like. The interview was originally published in Italian, in the Italian monthly magazine Horror, in December 1970 – January 1971. You can find more info about Italian horror movies in the monograph Vampires in Italian Cinema, 1956-1975 (Edinburgh University Press, 2020). If you are interested in buying the book, feel free to use the launch discount code EVENT30 for 30% off.

Mario Bava: Barbara Steele used to spend her days sitting around at Caffè Rosati [in Piazza del Popolo in Rome], with a pair of eyeglasses and a highbrow book, in the company of [Alberto] Moravia. I really don’t understand her. She had a career in front of her: she wasn’t a great actress, but she was allright. Then, she made a brief appearance in that movie by [Federico] Fellini and that was the end of it all… From that moment on, she began to reject all the job offers she received: she only wanted to be in movies of high intellectual value, but who would offer this kind of movies to her? So, basically, her acting career was over…

I am telling you about Barbara Steele because I launched her career (if I can say so) with my directorial debut La maschera del demonio / Black Sunday (1960). Do you know that I am going to shoot a remake of La maschera del demonio? I will discuss the project with some American producers tomorrow. They bought the rights of my old screenplay and they updated it a little bit. Now they want me to direct the remake of my own film. Why not? With all the overdue taxes I have to pay, I can’t afford to be picky with the projects I am offered. I accept any project, as long as the producers pay me straight away.

Of course, I sometimes get swindled, or I end up shooting movies that are not up to my usual standards. The case of [my film] 5 bambole per la luna d’agosto / Five Dolls for an August Moon (1970) is a good example, it went like this. The producers give me a screenplay, I read it and I say that I don’t like it, it is identical to [Agatha Christie’s 1939 novel] Ten Little Niggers / And Then There Were None. But the producers insist and, in the end, I accept to direct the film. I tell them that we will discuss the project in detail when they will pay me. So I start working on other things and I forget about 5 bambole per la luna d’agosto, until one Saturday morning the producers call me in their office, they give me my cheque and my contract, and they tell me that the shooting begins on Monday, in two days’ time. I take the money and I sign the contract, but I tell the producers that the screenplay isn’t good, that I need at least ten days to fix the story and make preparations… but, no, the shooting begins on Monday. So, in the end, what do I care? The film is done. It is a terrible movie, it certainly is the worst movie among those I directed. I couldn’t do anything about it, we were working under disastrous conditions, it was October, it was very cold, and most of the film took place at the seaside as if it was summer. I could only make two changes in the story. First, putting the corpses in the fridge was my idea (in the screenplay the corpses were buried and there were little crosses on the graves, just like in western movies!). Second, I changed the ending […] a little bit, but I don’t think that I managed to save the film. My daughter watched the movie in Padova, and she asked me if I had gone mad.

You see, my mistake is that I accept any job they offer me. Moreover, I am unable to take things seriously, I always feel like joking, and for the producers a director who makes jokes is unconceivable, incompatible [with the job’s duties]. But I have been in the film business for too many years now, just like my father [Eugenio Bava], who directed the mythological films of the silent era; I know everything and everybody [in the profession], so how can I take seriously this gigantic, absurd circus [baraccone]? But I have taxes to pay and I work with my own personal crew, my regulars – the camera operator, my son, the electrician… They have been loyally following me for the past twenty years… If I stop making movies, how will they make a living? So, let’s get on with the next movie!

With [my film] La ragazza che sapeva troppo / The Evil Eye (1963) I tried to make an experiment, a romantic giallo [giallo rosa]. I have been told that L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo / The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (Dario Argento, 1970) plagiarizes La ragazza che sapeva troppo… I can’t say if this is true, because I haven’t seen L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo yet. In any case, La ragazza che sapeva troppo is a romantic giallo: at that time I was recovering from a six-month nervous breakdown and I didn’t feel like shooting the film, but I needed money and I did the job. The only problem was that I found the film absurd as a romantic giallo. Maybe it could have worked with stars like Kim Novak and James Stewart, but my actors were… well, I forgot their names! So I started shooting the film in a very serious way, as if it was an actual tale of the macabre. When La ragazza che sapeva troppo was released, it even had a certain success.

One of the worst experiences in my life was the making of Diabolik / Danger: Diabolik (1968). I was shooting this film for Dino De Laurentiis, it was an important project and the distributors had paid 1.5 billion lire in advance [for the distributions rights]. But you know De Laurentiis, he is worse than the Ministry of Economy and Finance: the production company made me work for months and months (I, who shot Operazione paura / Kill, Baby… Kill! (1966) in twelve days!), and I wasn’t being paid for working overtime… Moreover, I had very little resources at my disposal, the final cost of Diabolik was 200 million lire. I had to come up with all sorts of cheap tricks because the production company didn’t give me anything to work with. Did you see Diabolik’s hut in the countryside, his hideout, his laboratory, the garage? I swear: they were all scale models, photographs that I cut out and pasted on a glass in front of the camera – an improvised solution that allowed me to make up for the misery of the whole scenery. And then, after exhausting myself with this kind of work, I also had to direct John Phillip Law, who wasn’t able to play the bad guy for more than thirty seconds… Finally, I told De Laurentiis: “How can we make a film about Diabolik without the bloody murders?”. But De Laurentiis didn’t want any violence in this movie because at that time there were trials against crime-themed comics [pubblicazioni nere] in Italy, and he was afraid [of censorship and legal repercussions]… Recently, De Laurentiis called me and asked me to direct a sequel of Diabolik. I sent him a message saying that I am ill, permanently confined to bed.

I wish that the audience and the critics knew the conditions under which I am forced to make movies. For [my film] Terrore nello spazio / Planet of the Vampires (1965) I didn’t have anything to work with. There was only a studio, completely empty and squalid, because there was no money: I had to turn that into a [mysterious, alien] planet. So what did I do? In the studio next door there were two big plastic rocks, a leftover prop from a sword-and-sandal movie or something. I took these two rocks and I put them in the middle of my studio, then I covered the floor with smoke and I darkened the white wall in the background. I shot the whole movie by moving the two rocks around the studio. Can you believe it? And, while I was shooting, there was this American screenwriter who kept rewriting the script, changing scenes and dialogues… After a while, I stopped listening to him. Do you remember that, at the end of Terrore nello spazio, the astronauts land on planet Earth at the beginning of its existence? Well, the screenwriter wanted the astronauts to get off the spaceship and meet Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, which was located in Missouri, USA. Naturally, I refused to shoot this kind of stuff.

Not to mention [my film] Ercole al centro della Terra / Hercules in the Haunted World (1961). I made a bet that I could make a feature film only by using a modular wall with a door and a window, and four mobile columns, without any other scenery. Therefore, I shot Ercole al centro della Terra by continuously moving these few elements around [the studio], in an endless series of shot-countershot. No spectator ever noticed. But my best film is Operazione paura… In Fellini’s episode Toby Dammit from the omnibus Tre passi nel delirio / Spirits of the Dead (Roger Vadim, Louis Malle, Federico Fellini, 1968) there is a ghost-child playing with a ball, just like in Operazione paura. I mentioned this similarity to [Fellini’s wife] Giulietta Masina, and she shrugged with a smile: “You know how Federico is…”, she told me.

A new film of mine, Il rosso segno della follia / Hatchet for the Honeymoon (1970), has recently been released. I shot it in Spain, in a villa owned by [dictator] Francisco Franco. The police didn’t want me to get the stairs dirty with [fake] blood, and the Spanish technicians drove me crazy… I will never go back there, I swear. But Il rosso segno della follia is a good film, I am quite satisfied with it. It is the usual story of a madman, but I could work on this project with calm and I prepared everything with meticulousness. You see, a long time ago, before starting my career in filmmaking, I was a painter, so now [that I am a director] I usually draw storyboards for my films. That is to say, I draw the whole film on paper, all the shots, all the cuts. This really helps me, but if the producers don’t give me time to prepare, I work almost blindly.

I have just finished another film, a comic western [titled Roy Colt & Winchester Jack (1970)]. It is a funny movie. Well, you won’t believe me, but the screenplay they gave me was very serious, very dramatic. I read it and I found it so grotesque and ludicrous that I decided to improvise stuff and make a comic film. Therefore, there was a lot of improvisation during the shooting. I wonder what the audience will think.

Besides remaking my own film La maschera del demonio, I have another project. It is titled Once upon a time there was a leaf… [C’era una foglia…], it is the story of a group of ghosts haunting a castle. The ghosts try to turn the perverted and evil lord of the castle (who is the last living member of an aristocratic family) into a good guy. It is yet another comic movie, full of humor. I wrote it myself and the shooting should begin soon. I have another story in mind, but for now it is just an idea: some crooks buy a destroyer from the World-War-Two years and sail around the world attacking ships like pirates. It would be fun, wouldn’t it? Meanwhile, I got another job. I made a series of sci-fi-style TV ads [Caroselli] for a big Italian oil company. I accepted this job because they pay really well. How could I refuse? […]